The invention of the flying shuttle.

For many the word shuttle is more likely to be a way of transport, or even a space age vessel, as its action so accurately describes the repetitive toing and froing along a pre-planned route. Yet the flying shuttle is a world class invention, being created by a humble weaver in the rural Essex village of Coggashall in 1733

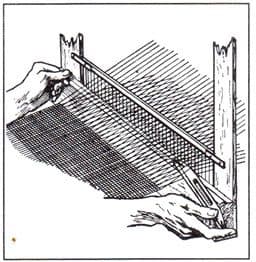

The life of the hand weaver since ancient times had been plied with the monotonous task of passing a hand shuttle from hand to hand via the cloth “shed” to make textiles. The shed is the opening made in the warp in order that the threads part in the weaving process. The speed of the process of hand shuttling was limited in that the hand shuttle was prone to direction change at any time in the weaving process, due to uneven weft tension. The throwing and catching of the hand shuttle relied upon the hand craft of the weaver and his skill in the manipulation of his thumbs and fingers in the throwing and catching process. In reality weaving speed was hardly an issue in the 18th century and if a figured cloth was made requiring a draw-boy to select the draw cords, the weaver would wait for the draw to be made before each shuttle movement.

Because the hand shuttle was passed from hand to hand the path of the shuttle was in the form of an ark rather than a straight line. To aid the passage of the shuttle the shape was curved and tapered at the ends to ensure an efficient action.

Between each passing the weaver would hold the shuttle in the hand whilst beating the weft into the fell (edge) of the cloth with the reed fixed in the baton. The gripping of the shuttle between the thumb and index finger for many years led to weavers thumb joints having considerable damage. It was against this back ground of repetitive hand work that John Kay the son of a hand weaver probably looked at his life before him thinking there must be an easier way to weave cloth.

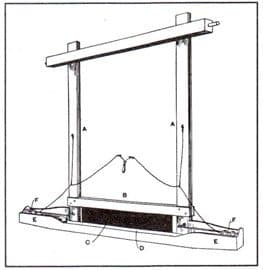

In the year 1733 he invented his flying shuttle which after being met with fierce hostility by his fellow weavers, who fearing the loss of earnings burnt his house to the ground. Kay fled to his native Bury in Lancashire where he succeeded in taking out a patent to protect his idea. Kay’s solution was to first apply a narrow shelf to the front of the baton where his shuttle could run. He attached wheels or rollers to the underside of the shuttle to eliminate friction and straightened the lines of it placing sharp steel points upon the ends. The speed of the shuttle was Kay’s most brilliant innovation in that he replaced the handling of the shuttle with a sling-shot mechanism which enabled the weaver to hold a handle and flick the shuttle from one side to another at speeds estimated up to 30 mph. At each side of the baton he provided a box for shuttle to rest in momentarily between weft insertions. A skilful operative of the fly shuttle could double the production of a hand shuttle weaver. Despite this step forward the invention was not initially liked or preferred by the English weavers but was quickly adapted by the French weavers who were able to sell cheaply in the English market. With the gradual use the flying shuttle more demand fell upon the weft spinners and winders to supply ever increasing amounts of yarn to fill the shuttle.

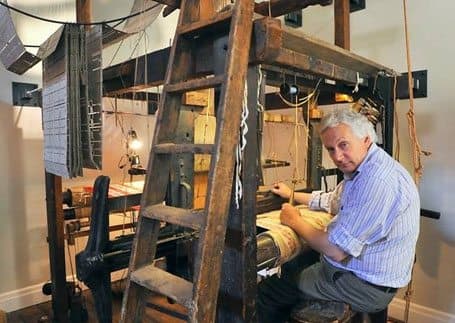

In 1760 Kay’s Son Robert added to his father’s success by inventing the drop box mechanism which enabled weft changes in additional shuttles to be added. The shuttle thread was pulled over –end from the spool rather than unrolling the yarn as with the hand shuttle. When Cartwright set about his inventing the power loom he set levers to pull leather straps to imitate the motion of the flying shuttle created seventy years earlier. As part of a £1.5 million refurbishment of the Bridewell Museum in Norwich Richard Humphries restored the 19th Century Jacquard Loom and fly shuttle with a drop box. The loom is believed to be the last of its kind remaining in the city which once had a thriving wool and silk weaving industry employing several thousand weavers.