The Quill, the Pirn and the Shuttle by Richard Humphries

A healthy goose in the 18th century was more than just for the table or the eiderdown. There was another important requirement for the silk weaver and his work as the quill, with the feather flights stripped off, was the ideal ready-made hollow tube for use in the shuttle.

Early Hand Shuttles

In order that the weft could be released from the shuttle during weaving, the thread needed to be carefully wound up in preparation. Early shuttles were thrown across the width of the with the flick of the hand. The hand shuttle could be straight and boat like with symmetrical ends or shaped with a curvature, as the path through the shed of the loom was in fact more ark shape than straight. The curve of the shuttle faced away from the reed, which is used to beat the weft into the cloth. To hols the quill inside the shuttle there was a hard wire sprung or wooden pin that fitted into a small hole in each end of the shuttle. As the quill was a ready-made tube, they could be cut to fit the shuttle aperture easily and discarded when they became split or dogged at the edges. The skill of the weaver was to cut the quill from the straightest part, so that the natural curvature of the feather spine was kept to a minimum, as this bias could affect the tension on the thread as it unraveled whilst in motion.

Paper quills were also made and adapted by weavers as a substitute to the natural quill. The rolling of papers created a fine and thin substitute to the natural quill could be made to fit the winding spindle exactly, which would enable a weaver to improve their production rate. Old Spitalfield quills in my collection (once carefully unraveled) show printed news of the time from magazines or journals. The inside diameter was around kept very tight, at around 3mm, to allow as much silk as possible to be wound onto the quill in one continuous length.

Clay pipes and ivory were also fashioned to be used in the hand shuttle as a further substitute. A full quill would have to be wound to give as longer length of weft as possible but so as not to be so full as to protrude above or below the shuttles profile. This was so that the yarn just missed any chance of abrasion of the warp above or below in the weave shed (the opening of the warp threads). It was these restrictions in the hand weaver’s time at the loom that all contributed to slower production; the revolving quill inside the shuttle, the limited length wound and the added tension by the speed thrown through the shed from one hand to another.

Lots of ingenious ways of speeding up the shuttle were tried and adapted. Wheels were inserted in the underside and hollowing out the centre to form thin side ridges could reduce friction. However the fact remained that the quill would have to revolve in the shuttle whilst it travelled through the weave shed. With these restrictions limiting progress it may have been yarn collapsing off of the quill end that led to a weaver redesigning the shuttle interior. This was a version of the hand shuttle that took the thread from a quill that was pushed on a spike, so that the yarn flowed over-end and out through an eyelet in the top of the shuttle, rather than from the side.

This idea was to completely change the hand shuttle, as the yarn could flow without the restriction of the revolving quill. With this idea the quill would not be a solution, as the weft would not be wound from a central start but instead from the base to the opposite end. This heralded the demise of the quill package to make way for the all new ‘pirn’, ‘plug’ or even ‘spool’. The pirn needed a tapering away from the far end in order that the weft thread would release and travel along the pirn whilst it unravelled.

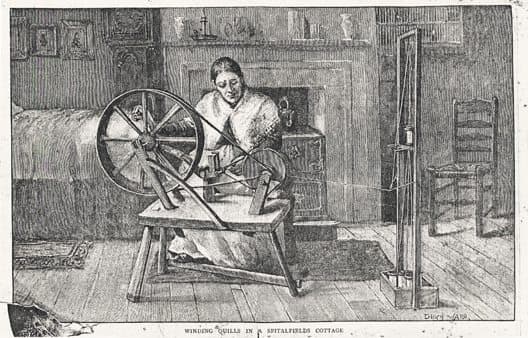

The pirn stayed fixed on the pin which was sprung loaded to lift upward to enable the changing of empty ones. By increasing the speed of weaving there was an increased demand for more weft, and more weft winding of pirn’s. A hand silk weaver would use between 60 to 80 pirn’s in a working day. The quality of the pirn winding was crucial to the success of day’s weaving and some weavers, being dissatisfied with the winding from their pirn winder, would rewind their pirn’s in an evening to ensure a perfect tension on the shuttle.

Winding a pirn that would not jam or collapse would be dependent on the skill in the build. By keeping the tension even as the yarn ran through finger and thumb, whilst the traverse built the yarn on the pirn in an even straight way, was the challenge.

The Fly Shuttle

John Kay’s flying shuttle was slowly adapted in the UK and this shuttle needed a fixed pirn to deliver the yarn into the cloth. The shuttle became increasingly more complex with tension springs, ceramic eyelets and sharp points (beaks) which in the silk trade had to be sharpened on an oil stone to ensure perfect shedding.

Read Richard’s full article on; “The Flying Shuttle”

The Power Loom Shuttle and Pirn

When Edmund Cartwright invented the power loom he speeded up the manufacturing process. With the shuttle moving much faster it became difficult to judge when to stop and when the weft had run out. Without a stopping motion the loom could continue with no actual weft going into the cloth. With the development of the weaving process came the idea that you could automatically stop the loom when the weft had almost run out. By creating a slot in the pirn and a matching slot in the side of the shuttle, a mechanical probe could be aligned to enter the shuttle side with each weft insertion. The weft covering the slot would hold off the probe, but when the weft has all but run out the probe enters the pirn and mechanically knocks the loom off thus stopping the process.

Read Richards full article on; “The Power Loom”

The mechanical stop remained intact throughout the 19th century but as the loom progressed so did the weft presentation. The adaptation from mechanical stop to electronic stop became more sophisticated with contact strips applied to the pirn base. This meant the strip had to be clean to conduct the completed circuit as two probes touched the surface.